The Big Fire

By Randall Brown

The summer of 1904 in California was hot and dry. Labor Day marchers in Santa Cruz sweltered under record high temperatures and the following day was hotter. Then, early Wednesday morning, the town’s electric system shut down. “All street cars were stopped,” reported the Sentinel, “and an almost weird quiet as of some impending calamity reigned throughout the city.” The appearance of plumes of smoke to the north compounded the anxiety.

In the middle of the previous night, a spark in the engine room of the Big Creek powerhouse had started a blaze which destroyed the flume that fed the generators. The nearby settlement of Swanton was quickly wiped out. Meanwhile, another fire, originating in a sawdust pit on Pescadero Creek, swept through the headwaters of Boulder Creek, igniting several thousand acres of timber belonging to the Cowell Lime Company. Summer residences, sawmills, and the tavern near the entrance to Big Basin Park were reduced to ashes. While the warden, assisted by men from a nearby mill, fought to protect the giant redwoods, a brisk wind pushed the blaze in another direction, toward the town of Boulder Creek.

Reports of new hot spots were telephoned in throughout the day. Embers from the Big Creek fire floated down the coast, setting off blazes in fields and wooded hills. Thousands of rabbits and squirrels ran frantically ahead of the blaze. Farmers and dairymen drove their cattle down to the beaches while crews of men from sawmills, ranches, and lime kilns fought to save homes and farm buildings. A fugitive from Davenport’s Landing reported that the conflagration had swept through every gulch and canyon, destroying a nearby sawmill and 30,000 feet of stacked lumber.

Before the end of Wednesday morning, much of Ben Lomond mountain was engulfed in flames. On his way to deliver the mail to the Bonny Doon post office, teenager Lee Smith pulled up short near the junction of the Empire and Ice Cream grades. “Suddenly,” reported the Santa Cruz Surf, ”a mass of flames shot forward, singeing the hair of the rider as well as his horse. Smith turned about and rode for his life with the flames at his heels.”

At times the firefighters seemed to be making progress, but they were frustrated by the quick moving flames, which leapt from treetops across open spaces to flash up hundreds of yards away. In the afternoon, the Ben Lomond blaze crossed the San Lorenzo river and raced through Quail Hollow into Lompico and the Zayante canyon, leveling all in its path.

“The chain of fire extends from the Big Creek country up the coast to the forests back of the town of Boulder Creek,” the Surf reported at the end of the day. “There are now six separate fires raging.” As the sun set, a reporter from the Sentinel observed that the smoke-filled sky had taken on “somber colors of red and purple—a strangely beautiful yet foreboding sight.”

Under a red sun, the fight continued on Thursday morning. First reports were discouraging. “The flames raged fiercely all night. It is estimated they cover an area now of over six square miles. The wind is more brisk than it was yesterday and as a result, the fire travels at a rapid rate and consumes everything with which it comes in contact.”

The people of Boulder Creek watched anxiously as a wall of flame approached the town. All able-bodied men and boys were pressed into service. “Every train is bringing fresh crews of fire fighters from outside towns,” reported the Surf, “who are being rushed to the scene of the conflagration.” A Southern Pacific track crew headed toward Big Basin but turned back when they realized that the bridges on the road were gone. Instead, the men spent the day protecting the Boulder Creek water plant on Foreman Creek.

All seemed lost for a time, as the fire moved through the canyon to within a few miles of town, annihilating houses on the way. Fortunately, the wind shifted direction during the afternoon, pushing the path of the fire back toward the coast.

Meanwhile, workers from the San Vicente kilns set a backfire to keep the Big Creek blaze from reaching the company’s storage yard, where several thousand cords of firewood were stacked. Further south, the grass-fed fires near Davenport’s Landing, having exhausted the available fuel, faded away.

All concerned were delighted when a fog bank rolled in from the ocean before dawn on Friday. “It came as a benediction,” according to the Surf. “Trees condensed it to a dripping dew, and before it the fire fiend wilted.” As the day went on, the small army of tired and blistered fire fighters gradually mastered the situation.

News finally came in from Bonny Doon, which had been hemmed in by fires on all sides for three days. “Whole families by bucket brigades and by a system of backfiring fought to save their homes, some with success, others were unsuccessful. The post office was in danger several times and the entire contents were removed to an open field.” Afterward it was discovered that someone had looted the cash box and made off with several rolls of stamps.

Summing up the damage, the editor of Boulder Creek’s Mountain Echo reported that: “Previous to the fire all of this country presented a beautiful park-like appearance, where perpetual springtime reigned, and that was really a pleasure to look upon. Today it is a blackened and ashy waste with more the appearance of a desert than anything we can liken it unto. Never before did we see such a transformation.”

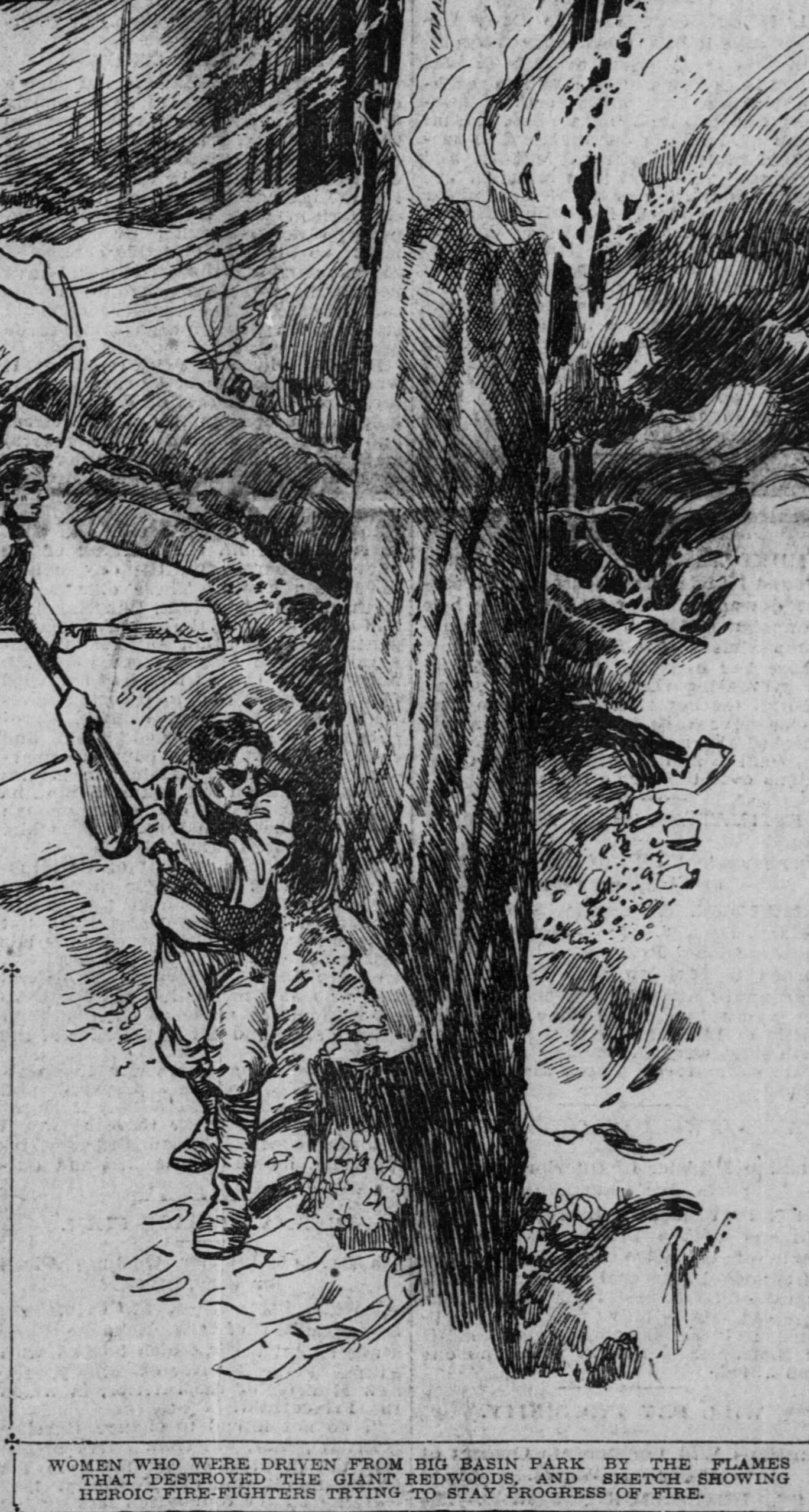

San Francisco Examiner drawing from Sunday September 11, 1904

Randall Brown is an author, historian, and San Lorenzo Valley resident.

The San Lorenzo Valley Post is your essential guide to life in the Santa Cruz Mountains. We're dedicated to delivering the latest news, events, and stories that matter to our community. From local government to schools, from environmental issues to the arts, we're committed to providing comprehensive and unbiased coverage. We believe in the power of community journalism and strive to be a platform for diverse voices.